New Orleans Post-Katrina: Making It Right?

by Rebecca Firestone with Mark English AIA | Editorials

“When I visited New Orleans last fall, there was no way to prepare myself for the despair I felt when walking through the Lower 9th Ward, even 6 years after the storm. What was most dismaying was seeing ‘celebrity architecture’ masquerading as sustainable housing. A vacuum of leadership at every level has left the task of ‘salvation’ to celebrities … with projects that are an exercise of vanity over practicality.

What place does LEED certification have in a disaster recovery if it makes construction so costly that only a handful of homes get built? Whose intentions are really more important?”

– Mark English, AIA

It all started when Mark English went off to a 3-day conference in New Orleans sponsored by Hanley Wood Media (which was a fantastic conference, by the way). What he had to say upon his return didn’t have much to do with the conference itself. He focused instead on efforts to rebuild in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward, which was devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. One particular high-profile rebuilding effort appears to be serving the vanity of its celebrity backers more than the displaced people it’s intended to help.

When I visited New Orleans last fall, there was no way to prepare myself for the despair I felt when walking through the Lower 9th Ward, even 6 years after the storm. Hurricane Katrina began as a natural disaster but has since become a manmade one, of epic proportions. A vacuum of leadership at every level has left the task of “salvation” to celebrities, and their private celebrity architects – with projects that are an exercise of vanity over practicality.

What was most dismaying was seeing “celebrity architecture” masquerading as sustainable housing. What place does LEED certification have in a disaster recovery if it makes construction so costly that only a handful of homes get built? Are we seriously expected to believe that a handful of LEED houses will somehow create a template for the future, even while the architecture itself destroys the porch culture that formerly characterized the close-knit social life of the neighborhood?

Whose intentions are really more important?

– Mark English, AIA

Why such harsh words? Well… consider this group, founded by Brad Pitt, called Make It Right. Make It Right intends to create a total of 150 LEED Platinum homes in New Orleans’ 9th Ward, where according to its own web site, closer to 4,000 homes were destroyed (another figure given elsewhere was 5,300 – the American Red Cross estimate is that a total of 275,000 homes were lost to Katrina but that’s statewide).

We feel that this is a wasteful approach, for several reasons. Although 150 new dwellings is a good start, each of these homes is costing two or three times as much to build as a less ostentatious building would. And taking longer, too. They’re all designed by prominent national architects, selected by invitation. This particular initiative was heavily promoted within the conference, including a carefully monitored bus tour where no contact with residents was allowed. In fact, no residents were present at the conference, either.

Disaster tourism came to New Orleans, too. But some people did stop to help, and stayed. Image source: Kathy Price

The residents are not invisible, however. They’re featured prominently in four pages of stories on the Make It Right web site – tough survivors who’ve never given up their dream of returning, saving up for their portion of the down payment required for these new homes. It would have been nice to speak with some of them directly to find out how they liked their homes, and to have their presence and input at the conference.

The consensus amongst our small group of conferencers was that the fancy LEED homes ignored the social fabric of the old neighborhood in subtle functional ways, thus providing a fragmented, expensive, and incomplete solution. In addition, many of the building features that may have originally been intended as functional appear to have become ornamental – more expensive to build and less effective.

The Great San Francisco Earthquake Disaster Response: A Comparison

Compare the New Orleans rebuilding to another effort that took place here in San Francisco after the Great Earthquake of 1906. At that time, the priority was to create as many housing units as possible, as quickly as possible, and the solution was the now-historic earthquake cottages that continue to dot the landscape. These cottages were small, portable, and they did the trick, all without name-brand architects or LEED.

Following the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, the City built over 5,000 portable earthquake cottages within a year, and housed people in refugee camps like this one in the Presidio. Some are still around today – the right photo shows an interior remodel of a San Francisco earthquake cottage by Klopf Architecture.

The above-mentioned site describes both the speed and efficiency with which the first-response tent camps, established over the spring and summer following the earthquake, were transitioned to shacks for those still homeless:

As winter approached, the city built 5,300 small wooden cottages for those still in need of housing. These “earthquake shacks” were a joint effort of the San Francisco Relief Corporation, the San Francisco Parks Commission, and the Army. Union carpenters built the structures, which are said to be based on a design provided by General Greely, who had personal experience in building Arctic shelters with few supplies… At peak occupancy the cottages housed 16,448 refugees. Tenants paid $2 a month toward the $50 price of the cottage. After paying off their new home, the owners were required to move their cottages from the camps. The last camp closed in June 1908, leaving earthquake cottages scattered throughout San Francisco…

The Make It Right initiative didn’t go for simple pedestrian solutions designed by Army engineers. Nor did they sponsor an open design competition. Instead, Brad Pitt teamed with Graft Architecture and two other firms, to assemble a list of hand-picked “name” designers. Although the criteria included an interest in New Orleans and sustainability, the resulting designs often look like they’re from Mars.

The San Francisco built 5,300 cottages in under a year, while comparable efforts in New Orleans don’t seem to have completed anything close to that. Habitat for Humanity has built around 80 homes (Musician’s Village), Make It Right has completed around 60 out of 150, and there are other groups less touted that are building on the same scale in surrounding areas like Pearlington, MS.

A few months ago we interviewed Richard Best, an architect who had worked in Dubai and was then seeking to join with Architecture for Humanity in order to work on rebuilding the earthquake destruction in Haiti. What he said at the time was something that would seem to make sense for New Orleans as well:

For Haiti… our plan… involves a couple of stages. First, we want to get the survivors into palatable living conditions as quickly as possible. This means moving them away from the rubble into immediate shelter, so that we can remove debris safely and lay down new infrastructures. Since the reconstruction may take several years, we might need to move people again so that they have someplace to live in this interim period which could be 10 years. So, one idea is housing that can move, can be transportable, but will still provide shelter from hurricanes.

As in the San Francisco earthquake, a possible solution involves moveable housing, but without the hugely expensive foundation work.

Leaderlessness at Local and National Levels

Another difference between San Francisco in 1906 and New Orleans in 2005 is that some experts and authorities suggested that New Orleans was not worth rebuilding, due to its challenging wetland topography – more on this later. In addition to a leadership gap at local planning levels, there was perhaps political indifference on a national level towards a region that the then-in-power Presidential administration did not count amongst its strongest supporters.

Richard Campanella, Assistant Research Professor in the Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences at Tulane University in New Orleans, put it into a wider perspective:

The rebuilding of New Orleans is a vast decentralized undertaking being executed an/or funded by a weakly coordinated cast of players that includes individuals, neighborhood associations, volunteers and foundations, the private sector, the city, the state, the Federal government, and even some international entities. MIR is simply a high-profile example… a very famous micro-scale demonstration project involving a handful of families – but no more.

So, what was there prior to Katrina?

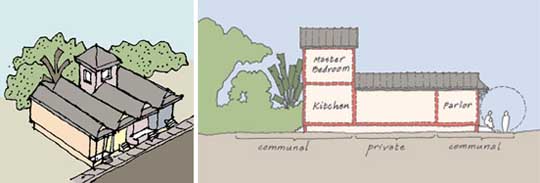

In New Orleans, the 9th Ward is a peculiarly isolated place. Steps from downtown, it’s cut off by a canal with drawbridges that can stay open for half an hour at a time. And yet, stories abound describing its stable, neighborhood feel. 80% of the residents owned their own homes, some having been there for generations. A strong tradition of local activism also seems to have continued. The architecture and layout was highly regular: single or double family shotgun cottages, only 6 feet apart, with generous front porches and modest dimensions of 800 to 1200 SF.

This photo from Kathy Price shows a row of houses that were restored after Hurricane Katrina. The colors are brighter, but the original architecture is the same.

The porch was probably the most visible and certainly the most socially functional feature. Generous overhangs protected the house from the sun’s heat and the rain, and especially prior to the days of air conditioning, it was likely the most comfortable place to be in the summertime. People would sit on their porches, conversing across houses, watching the street, facing outward.

This image from Kathy Price shows a restored Victorian from New Orleans’ 9th ward. The vertical windows make the house seem taller and grander.

The other observation we had was that the homes appear to be clustered together with large gaps between, and no commercial strip or local services. Given that it can take upwards of 40 minutes to drive anywhere from the 9th Ward, it seemed strange that so much attention had been paid to the individual nature of every building, and none to overall neighborhood patterns.

It should be noted that many of the residents whose homes were destroyed either had no insurance, or have had great difficulty in obtaining insurance reimbursements. They may still own the plots of land – which I’m told are worth about $5K apiece – but, without capital, they’ll need assistance of some sort to return.

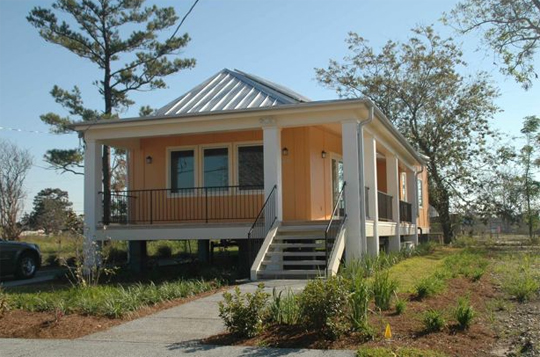

This example porch is closed off on the sides, and also can’t be entered from the yard or street. If the owners want to run to the neighbors, they’ll have to go inside the house and then out the side. Note the expressive (and expensive) canopy on the left that is meant to shade the side of the home.

What’s so wrong with the designs, anyway?

It may seem nitpicky to focus on a design critique when the overwhelming importance is of course to restore life and habitable dwellings, but this IS a design blog, so let’s get out our magnifying glasses and have a go.

Before: Houses were all lined up, same size same level, with open porches that encouraged communication. “It was very democratic,” says Mark English, again expressing a general consensus among the conference-goers.

Now: In the new scheme, the houses all seem to be at different levels, with different setbacks from the street. The porches on the new homes are sometimes blocked from the side. In other parts of the country, the “inward looking box” is the ideal – privacy trumps street awareness. But those other regions don’t have the same close-knit community feel, either.

Before: Porches actually shaded occupants from both sun and rain. The buildings themselves were also protected from the sun’s summer rays.

Now: In the home on the left below, the screen doesn’t actually shield the building. It’s purely decorative – often at a disproportionate cost. The house is probably super-insulated at least, so it shouldn’t need as much shading, but still… In the home on the right, the overhang has been minimized and is so high up that it can’t provide either shade or rain shelter.

Sidewall shading devices ore of questionable utility, and amazingly expensive. Mark English asks, “Would they even be necessary if the houses were sited to shade each other?”

Before: Roof lines were modestly pitched.

Now: Roofs are more steeply pitched, and more elevated, ostensibly for solar panels, but we think it might also be to allow the designing architects to play more with volumes. Also, a roof designed for solar panels should be pitched to take advantage of the sun’s highest position within the home’s particular latitude.

Before: Roof lines were conventionally angled.

Now: The roof on this house below looks like it’s falling off. It’s more expensive and harder to construct, too. Mark English adds, “Is this design device worth the extra money in this setting? What is the architect saying? I thought the most important function of a home was to house a family.”

This design looks very authentic from the front, but this side view shows the roof tilted at a cockeyed angle, which could add to the difficulty and cost of construction.

Before: Houses were so close together that there was no point in ornamenting the sides, because they’d never be seen. Almost all of the ornament was in the first 10 feet of the house.

Now: This siding, both in shape and openings, is an architectural statement having little to do with local convention.

We felt that this siding served the purpose mainly of making a clever design statement. Its impact will be lost if other homes are built at the original spacing of 6 feet apart.

Here’s one house that actually references local vernacular. Not surprisingly, it’s by a local firm. Its wraparound porch has an overhang that actually shades the house, and anyone sitting outside.

This design is the closest to the original styles. It’s got a slightly tilted roofline when seen from the side, but the essentials are here: the generous wraparound porch shades the house, and shelters anyone sitting out there on a rainy day.

The Floating House Folly

Here’s one thing that really set Mark English off: a nifty pylon system by Morphosis that allows the house to float in the case of a flood. Check out this video. Well, what’s wrong with that, you ask? Flood-proofing would seem as obvious to New Orleans as quake-proofing is in San Francisco… but is that really a cost-effective solution?

“We have flood-proof housing right here in Sausalito,” answers Mark. “It’s called a houseboat.”

But why do we have to exactly restore what was there before?

If we as Modernists are trying to get away from fake Tuscans in California, why try to replicate an archaic gingerbread-y vocabulary in New Orleans?

We don’t have to create new homes that look identical to the old ones. It’s better to keep the forms simple, and allow the owners to customize things through color or other additions and features. What’s more important is to preserve the needed functionality – and in some sense or fashion, the proportions and scale.

Why are architects from other places criticizing the authenticity of a neighborhood they’ve never even lived in?

After a more careful review of the material I’d have to say that even vanity rebuilding is a whole lot better than NO rebuilding… and publishing the homeowner stories at least legitimizes their existence and involvement in the process. It’s clear from these narratives that all the people who chose to return had deep roots in the area, and it also puts the personal tragedies into perspective. It may be mainly other architects, who know what could be done better, who find aspects of Make It Right’s approach so objectionable.

What’s wrong with making the new homes LEED certified?

The LEED designation may cut drastically on monthly energy bills – one writeup on the Make It Right site claims a cut from $250 to $35. However, the two main critiques of LEED, especially from a residential perspective are the following:

- The certification process itself is highly cumbersome and expensive, up to $15,000 just for the certification – and that’s per house.

- LEED has no requirements for post-construction verification that actual energy use is as low as anticipated. This has led to some embarrassing moments with LEED buildings that turned out to use just as much energy as any other building, and also LEED-certified buildings with counterintuitive functions that don’t support environmentalism, energy conservation, or renewable energy. Who ever heard of a LEED-certified gas station? And yet, there is one.

Where are the original residents now?

Here’s where it gets even more interesting. Remember how we hinted that no one cared about the 9th Ward because they were “low-income” (as if Kanye West didn’t blurt it out first thing)? According to Tim Culvahouse, FAIA, a prominent architect and educator, many of the Katrina survivors declined to move elsewhere in the city, into currently available housing because they were too attached to their one plot of land.

As Culvahouse tells it, back in 1979 New Orleans had a program to revive tens of thousands of abandoned homes that existed in the city at that time. These were usually places where the owners owed unpaid property taxes. The city allowed interested third parties to take over these homes as long as they were willing to pay the back taxes. The new occupant of the abandoned home could then fix it up, live in it, while the original owner still had 2 years to repay the occupant for both the back taxes AND the current market value of the improvements.

Apparently many of these blighted homes are still around and available. So why didn’t the Katrina survivors take the city up on it? Well, according to Culvahouse, some may have preferred to keep living in exile rather than give up “their” land that had been in the family for generations, while others may have returned, but to other parts of the city. He subesquently added, “What is certain is that the ones who have rebuilt in the Lower Ninth, either on their own or with some help, have chosen the relative exile of that essentially rural landscape over life in the city.”

This design at least doesn’t look like it’s from Mars. If that porch were a bit more shaded on the top you could probably shelter from the rain and sun. Now if only the porch could wrap around to meet the stairs…

What about other organizations?

There are probably several local groups that don’t have web sites or press releases. Here are a few that do, although it’s hard to find out how many homes they’ve completed or whether those homes are occupied.

Holy Cross Neighborhood Association – The Holy Cross neighborhood is a historic district within the 9th Ward. The HCNA works for sustainable rebuilding and restoration, with a community-centered approach. I don’t know that they’ve actually built anything themselves.

Habitat for Humanity New Orleans – A worldwide Christian-based organization with local affliates, the New Orleans Area HFH has built 418 homes since 1983, but no information on how many of that total were post-Katrina. However, their “Musician’s Village” project provided 72 homes specifically for New Orleans musicians following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. (They look a lot more like the originals, too.)

Musicians’ Village was a set of 72 homes built by Habitat for Humanity in New Orleans following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

Historic Green – They’re rebuilding with attention to historic preservation in N.O’s Holy Cross neighborhood, in partnership with the U.S. Green Building Council.

Global Green – This was the U.S. arm of an international company (founded by Gorbachev!) doing legitimate energy consulting and sustainability work. Our observers have reported that this group built a few green showcase homes but the scuttlebutt at the conference was that no one had purchased them because they were too unattractive. An interview with Matt Petersen, president of Global Green USA explains more about their goal of showcasing sustainable architecture.

ACORN – Well, they’ve since been heavily shellacked in the media, but their volunteers did build two houses. Which people are living in.

One has to wonder, though, why private organizations and government agencies don’t focus more on empowering the residents to return, and perhaps aid them in navigating the financial and legal systems in order to do their own rebuilding. Could it be that the City of New Orleans doesn’t really want them back?

On Vanity Philanthropy

So, why didn’t Make It Right make it a priority to get as many people as possible back into clean, efficient housing? One observer attributed this to a combination of leaderlessness at the local Planning Department, and to the egos of the architects and celebrity sponsors – all of whom would like to swoop in and create something heroically glorious. The real work comes AFTER the buildings, with the gradual restoration of the social fabric over time.

And why does Brad Pitt’s name and image need to be everywhere on the Make It Right web site? It puts displaced persons on display as an object of charity, with star billing reserved exclusively for the donor. Rudyard Kipling’s famous call to “take up the White Man’s burden” is part of what this NY Times article calls the “Western fantasy of omnipotence”, where wealthy nations may have a genuine wish to relieve suffering, but are hampered by their own belief that with enough money they can “fix” everything.

Many other celebrities have gone in for humanitarian projects – Madonna, Paris Hilton, Bono, Oprah, Bill and Melinda Gates, Richard Gere. When Paris Hilton suddenly developed an interest in Africa, people were more willing to believe that she was simply a pampered socialite trying to beef up a drug-tarnished image. It may depend on how savvy and sincere the founders themselves are – and how focused. Some of the most effective givers aren’t known at all outside of their own communities.

Direct Charity Makes Poor People Poorer

I took a closer look at some other well-known celebrity foundations, notably the Gates Foundation from Bill and Melinda Gates, and also the Skoll Foundation, founded by Jeff Skoll of eBay. Both these foundations don’t do direct action themselves – instead, they give grants according to well-defined criteria that support the mission and beliefs of their founders. They’re not just dashing from one humanitarian disaster area to another. And, the Gates Foundation does a lot of follow-up to see how well things are working – something that’s often ignored in international aid efforts, where it seems that the more money is poured in, the less local concerns are heard. The only people who benefit are the Halliburtons of the world.

Kathy Price Blog

In our searches for images among other things, we found a blogger named Kathy Price who started with a remodeling blog, but who eventually moved to the 9th Ward after seeing the devastation. She’s written reams about her subsequent involvement in neighborhood activism – not as a self-promoter, but as a reporter and preservationist on the spot who seems willing to walk the walk. See her entry from December 21, 2008.

She’s pretty bullish on the Make It Right people, and also has a big focus on color design that’s very interesting and informative. And her Green Building thread is worth a read, too.

Other Design Critiques

Tim Culvahouse writes about effective patterns and local typologies including “camelbacks” and shotgun homes, saying that the Make It Right houses are “putting the chariot before the cart” and “will not form the coherent streets so beloved — and so highly functioning — in New Orleans.”

Another publication, Cite Magazine published quarterly by Rice Design Alliance in Houston, has an interview that explores some of the same questions we’ve raised here.

The MIR Founding Architects

The core design team for Make It Right included at least three firms: Graft Architecture, William McDonough + Partners, and John Williams Architects, LLC.

Graft is actually only one of several architectural firms selected by Brad Pitt as part of the core design team, but they seem to have had a great deal of influence upon the aesthetic direction. After reviewing so many comments about the lack of local sensibilities I was surprised to see a fair amount of lip service paid to just these very things in Graft’s own writeups (which are best found in various entries on e-architect.co.uk rather than on their own highly annoying, Flash-infested web site).

Graft Architecture proposes this as a modern interpretation of the “camelback”, a traditional New Orleans typology.

Here’s what they have to say for themselves:

…we have additionally drawn inspiration from the camelback shotgun typology. Historically, camelbacks emerged as a way for residents to add a partial second story to a residence… In our design, we utilize the camelback strategy to stack a second efficiency unit above a first floor shotgun house.

Tim Culvahouse talks about camelbacks in his critique referenced immediately above – he says it’s ignored, but it looks like it’s still around, in some form or fashion. Graft goes on to describe exactly how they are indeed referencing local features like the porch culture:

A critical programmatic goal within the design is to establish a strong connection between the private interior zone of the house and the shared public space of the street. The primary challenge in achieving this goal lies in negotiating the 8′-0″ first floor height that is required to make the houses safer from future flooding of the street level. The broad and spacious deck located in the front yard mediates the relationship between public and private by raising the deck 5′-0″ above grade. This offers a welcoming gesture to the street while at the same time creating a semi-private space for the inhabitants of the house to enjoy.

So, I dunno. Here’s Culvahouse’s vision of the camelback.

I tried unsuccessfully to contact a spokesperson from Graft, but it appears from their literature that they did recognize the former neighborhood’s “atmosphere of engagement” and they tried to keep it, but also to inject a Modernist vocabulary. Maybe that was a vanity move, but a lot of thought went into it.

Speaking of vanity, Graft does have a lot of unbuilt work that looks highly idealistic and futuristic, as if Zaha Hadid had gone into sustainable design, and they also are building some LEED certified luxury resorts – sustainable luxury resorts seem a bit of an oxymoron, but someone’s gotta do it. After all, we may reason, those resorts would be built regardless, so why not make them a bit more environmental (or a bit less damaging, depending on how you look at it)?

The other two firms seem to have more realistic bodies of work and relevant experience – although looking at their beautiful contemporary residential designs does make me wonder whether their vision of sustainability could ever be coupled with affordability.

The Four Questions We’d Really Like to Ask Brad Pitt

We’ve been trying (unsuccessfully – surprise!) to contact both Brad Pitt and the Make It Right executive directors to ask them a few of the questions posed in this article. Until we hear from them, here are the four questions we would like to ask them directly:

- After Katrina, over 4,000 homes were lost in the 9th Ward, yet you’ve chosen to build only 150 new homes, all by big name architects. Wouldn’t it be cheaper to make the designs less self-conscious, keeping the flood-proofing but ditching the crazy designer roof angles, and let the homeowners customize them later on? You could have built a lot more houses for the money that way.

- It’s a common critique within the design community that LEED itself is expensive and not worth the money for private residences, so why pursue LEED certification, instead of putting that money into building more homes?

- How much attention was paid to the local social fabric – the “porch culture” – in relating one home to the next, or to providing shelter from rain and sun to keep the porches actually usable? On many of the porches, the shading is often so high up that there’s no shelter from the elements. What sense of community will there be if the homes are too closed off from the street and from the adjoining neighbors?

- How much attention was paid to creating livable neighborhoods, not just homesteads? Did you consider planning for services such as a viable and accessible commercial strip?

We’ll update this article if we ever hear back ;-0

Geography as Destiny

Having argued back and forth about modernism, sustainability, vanity architecture, there’s still one more thing to cover: geography. When national authorities determined that New Orleans wasn’t worth rebuilding, it wasn’t just racism talking. Professor Richard Campanella, mentioned earlier, possibly knows more about the geography and settlement history of New Orleans than anyone.

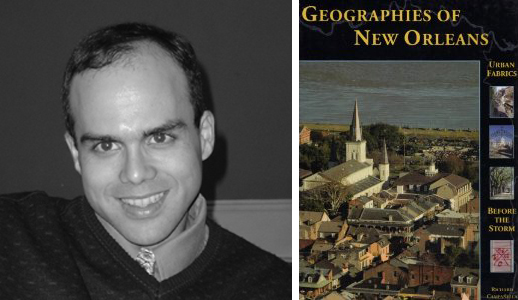

Among his books is Geographies of New Orleans: Urban Fabrics Before the Storm, a thorough analysis of the settlement history – architectural and cultural – of each neighborhood. It’s a bit like Edward Tufte’s classics on envisioning information – massive amounts of research expressed in statistically elegant graphs showing, for example, not only how many Jews or Creoles lived where – but the likelihood of that information being correct. Meticulously honest, respectful, thorough, and non-partisan, Campanella might be the most authoritative voice of all regarding New Orleans history.

Richard Campanella, Research Professor in the Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences at Tulane University, and author of the book Geographies of New Orleans: Urban Fabrics Before the Storm.

We sent him an earlier draft for his comments, and he has most generously allowed us to quote him here at length.

I would point out that, well, it’s Brad Pitt’s money. He can do whatever he wants, within the limits of codes and laws– and he broke none of them. He could have spent it on silly hats or jetsetting to Cannes. True, he raised money through his foundation, but to my knowledge, that was all private money as well. So in my view, MIR has a certain level of license to be creative, utopian, innovative, and perhaps a little zany, and may be forgiven if its efforts eventually prove to be inefficient and ineffective. It would be a very different story if this were public money…

I’ll leave the architectural criticism (stylistically and structurally) to architects and designers, and I’ll leave the civic-engagement criticism to the sociologists. What I, as a geographer, can opine on is the decision to build MIR at that site, precisely in front of the high-velocity breach flooding, on land that is mostly below sea level and adjacent to two risk-inducing manmade navigation canals. This was a bold, high-minded, and morally majestic decision, but a foolish one. It reflects a romanticized notion of the relationship between place and people (culture). It indulges in the tempting (and popular) but problematic presumption that “place makes people,” whereas in fact the opposite is more commonly the case. It attempts to “save” the culture of that neighborhood by rebuilding in that exact spot, as if culture emerges from soil. The truth is that human beings adjust their place all the time. They move to different houses, neighborhoods, cities, states, nations, and continents incessantly. Most of the pre-Katrina housing stock near the MIR project only dates to the 1920s-1960s; residents moved there from other neighborhoods only a couple of generations ago, at most.

More troublingly, MIR’s site selection decision reveals a breezy arrogance (note the name “Make It Right”) and a misguided sense of defiance. At whom are they shaking their fists by insisting on making their statement at that unsustainable site? Global warming? Under-engineered levees and floodwalls? Centuries of delta urbanism and their deleterious impact on the landscape? The whole Katrina tragedy?

Make It Right seems to be more interested in making garbled political statements and basking in the glow of progressive righteousness, than in building a maximum number of reasonably sustainable low-cost houses in a sustainable location. I personally identified over 2000 open parcels of above-sea-level land in the heart of the New Orleans historic district. That’s where MIR should have built. And it is from those neighborhoods that most residents of the Lower Ninth Ward can trace their roots.

If you build sustainable structures but place them in a geographically unsustainable site, have you really “made it right”?

17 Responses to “New Orleans Post-Katrina: Making It Right?”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

andrew sloan kelly

28. Jan, 2011

fwiw, mark, i completely agree with you on this brand of new orleans sustainability and reconstruction. many, including a good number or residents, see this vanity versus practicality exercise quite plainly. while any attention brought to the needs and problems of new orleans is good, the message is heavily obscured.

it is the most wonderful of places, and deserves much more than floating houses and “starchitecture” muscle-flexing as a response to a legitimate civic, environmental, and human concerns. kudos!

William Monaghan

22. Feb, 2011

Build Now is the largest non-profit home builder in New Orleans that is constructing new houses for homeowners whose homes were destroyed by Katrina, on their lots. We build socially and environmentally responsible houses in the traditional New Orleans Greek Revival style. To date, 43 houses. We help homeowners find the programs, mortgages, and resources they need to build a house, and then we build them a new, elevated, Energystar-rated house for an average subsidy of $20,000 per house. Please visit http://www.buildnownola.com to see our houses.

Willy Monaghan

David Andreozzi

23. Feb, 2011

Mark & Rebecca,

Fantastic read, thank you. I had a similar reaction and posted on the AIA discussion Board here http://network.aia.org/AIA/AIA/Discussions/ViewThread/Default.aspx?GroupId=1771&MID=1325

CJSteward

14. Mar, 2011

Unfortunately, Mr. English’s comparison to existing Lower 9th Ward architecture is faulty, as the remaining houses in the area are predominantly in the historic Holy Cross area of the district, which predates the upper northern portion of the area that was so drastically affected by the flood wall failures. The area that MIR is rebuiliding, was predominantly mid-century suburban style houses that did not share the charming front porch style of historic New Orleans neighborhoods. The northern portion of the Lower 9th Ward, which is still predominantly empty, was architecturally much more inward looking than the examples given in the review. No argument with many of the complaints about the actual MIR houses, but perhaps a bit more research into what the neighborhood actually looked like would be helpful…

Mark English, AIA

14. Mar, 2011

Thank you for your comments, CJ Steward. My comments regarding the “architecture” or Urban Planning portion of the article were based upon the premise that MIR states on their own website:

“Single Family Homes

Updates to a Classic

The thirteen architects who contributed to single family home designs all hewed to the traditional New Orleans shotgun house format – simple, narrow and fashioned to fit the long skinny lots in the Lower 9th Ward. They also all include porches – a feature highly valued in the neighborhood that places a premium on sociability and connectedness to the community. All of the homes have more complex floor plans, solar panels, rain water collectors and other green features.”

As an interested colleague, my first critique will always be “did they follow their own premise?”. No, they didn’t in my opinion.

The bigger question of whether the premise was even correct, I leave to Richard Campenella.

Eugene

27. Mar, 2011

Fascinating read. Shameful that 6 years on there still seems to be no coordinated effort to fix this mess.

The Indicator: The $5000 House | ArchDaily

19. May, 2011

[…] (as some argue occurred in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward when architects were brought in to help rebuild).Via http://www.strykerahc.orgSo for that 30% of the homeless population comprised of families, is it […]

Dan Matarozzi

08. Jun, 2011

Mark and Rebecca,

Excellent observations on the rebuilding in NOLA. Historically, it is no accident that poor people ended up in places like the Lower 9th Ward. The rich planters who owned the town built on the highest ground available to them Their plantation houses and the ornate mansions that succeeded them can still be seen if you take a ride from Canal St. on the St. Charles Avenue Streetcar. By some

accident of nature, had these wealthy sectors been decimated and the 9th Ward been spared, I don’t think anyone would argue that the fundamental nature of the response to the tragedy would have been the same. Money and manpower and the will to rebuild would have been summoned in a relative heartbeat. The tone deaf LEED structures that filled the void in the Lower Ninth are isolated canaries in the coalmine, pointing towards a systemic problem of how wealth is created and where it ends up.

Building Social Responsibility…Right | Metropolis POV | Metropolis Magazine

20. Jun, 2011

[…] Foundation’s (MIR) agenda provides another example of good intentions gone awry. An excellent editorial by Rebecca Firestone details the exact issues plaguing the proposals. One problem is the siting of […]

Handybilly

12. Sep, 2011

Part of the problem was that Missippi is so caged in that it can not flood and deposit silt on the outer islands. this did not help

this situation.

mr pitt

09. Mar, 2012

my mother have a double to renovate and i was wondering if someone can give me some ideas on what to do with this property. i saw that yellow cottage house with porche raped around and i wondered how much it would cost to build this house,or renovate the one that is still standing or call and get prices for a prefab house if anyone can help me through around some idea i would like this i meconnie c@yahoo.com thank u mr pitt

nola news « NewOrleansBreeze

11. Mar, 2012

[…] One in particular featured an article titled New Orleans Post-Katrina: Making It Right? (https://thearchitectstake.com/editorials/new-orleans-post-katrina-making-right/ ) I actually follow this blog semi-frequently because it is an architecture blog, but I appreciate […]

Design Ethics in Disasters — AIACC

23. Oct, 2012

[…] a related perspective, see Mark English’s “New Orleans Post-Katrina: Making It Right?” on The Architect’s Take, source of the images […]

chuck

11. Jan, 2013

very interesting…because of the past connections…the ancient stuff in New Orleans with high ceiling and the large walk-thru double-hungs did offer a sense or responding to the local scene that all this LEED nonsense does not….lived there and did that but not in the Ninth Ward…and of course the landscaping in New Orleans is something else…have not been back since 79

New Orleans Rebuilding: Could Topography Make It Right? | The Architects' Take

29. Jan, 2014

[…] year ago, we published an editorial critique of some of the post-Katrina rebuilding efforts in New Orlean’s Lower 9th Ward, specifically […]

6 People Who Responded To Tragedies In The Most Soulless Way - gribl

25. Aug, 2015

[…] This may come as a knee-buckling surprise, but New Orleans residents are not exactly jazzed about having their lives take center float in a parade of misery for sociopathic tourists. So they do what they can to make sure these sightseers realize what tumbling shitlords they are. Some of the signs invite the tourists to leave their buses (which most tours do not allow them to do) and help the fuck out. […]

rpsabq

16. May, 2019

I read many times about “charity” and “Brad Pitt’s money” etc. These people weren’t GIVEN anything. They had to BUY these houses. These people have mortgages just like the rest of us. That’s what makes this so wrong.